When your pharmacist hands you a generic pill instead of the brand-name drug your doctor prescribed, you might not think twice. But behind that simple swap is a complex legal and scientific system designed to ensure safety, consistency, and cost savings. At the heart of it all are the FDA therapeutic equivalency codes-a set of letters and numbers that tell pharmacists, doctors, and state regulators whether a generic drug can legally replace the brand-name version without risking your health.

What Are FDA Therapeutic Equivalency Codes?

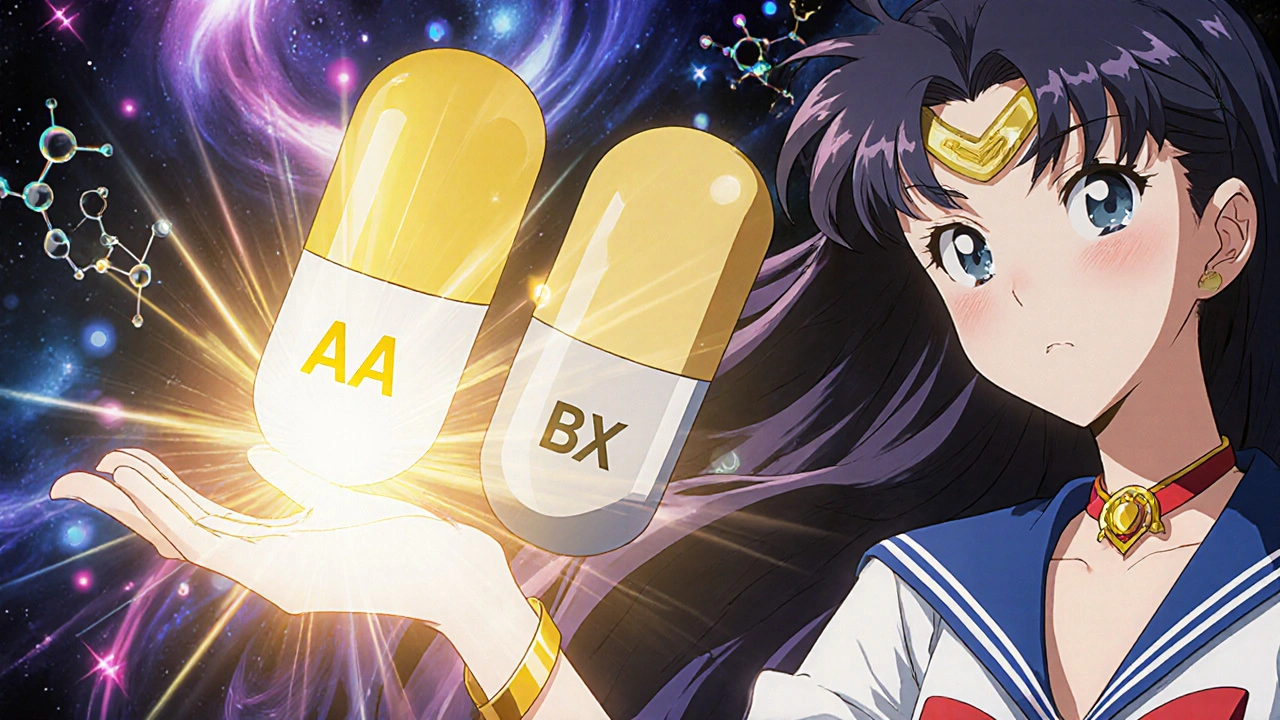

These codes, known as TE codes, are assigned by the FDA to every multisource prescription drug listed in the Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, commonly called the Orange Book. First published in 1980 and expanded after the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act, the Orange Book is the official federal guide for determining if a generic drug is interchangeable with its brand-name counterpart. The TE code is a two-character alphanumeric label. The first letter tells you the big picture: A means the FDA says the generic is therapeutically equivalent to the brand-name drug. B means it’s not. The second character gives more detail about the drug’s form or any lingering scientific questions. For example:- AA = Immediate-release oral drug with no bioequivalence issues. This is the gold standard.

- AB = Originally had questions, but later proven equivalent after more testing.

- BT = Topical product (like a cream or ointment) with unresolved bioequivalence concerns.

- BN = Nebulized aerosol product-hard to test for equivalence because delivery matters.

- BX = Not enough data to judge. Not approved for substitution.

How the FDA Decides Who Gets an ‘A’ Code

Getting an ‘A’ rating isn’t about matching the pill’s color or shape. It’s about proving the generic drug does the same thing in your body as the brand-name version. The FDA requires three things:- Pharmaceutical equivalence - The generic must contain the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form (pill, injection, etc.), and route of administration (oral, topical, etc.) as the brand-name drug.

- Bioequivalence - The generic must deliver the same amount of active ingredient into your bloodstream at the same rate as the brand. This is tested in clinical studies with healthy volunteers.

- Identical safety and efficacy - The FDA reviews all available data to confirm the generic produces the same clinical results and side effect profile.

Why ‘B’ Codes Exist-and Why They’re a Problem

Not every generic gets an ‘A’ code. About 24% of FDA-approved multisource drugs still carry a ‘B’ rating as of October 2023. These are mostly complex products: extended-release pills, inhalers, topical creams, injectables, and nasal sprays. Why? Because testing bioequivalence for these drugs is hard. A cream might look the same, but if the active ingredient doesn’t penetrate the skin the same way, it won’t work the same. An extended-release pill might release the drug over 12 hours, but if the release pattern is slightly off, it could cause side effects or reduced effectiveness. The FDA admits this is a challenge. In 2023, they launched the Complex Generic Drug Initiative to reduce the number of ‘B’ codes. Since 2018, the average review time for these complex generics has dropped from 34 months to 22 months. Still, only about 1 in 20 complex generics currently gets an ‘A’ code. Pharmacists are cautious. A 2023 survey found that 68% of pharmacists hesitate to substitute topical products with ‘BT’ codes-even when the FDA says they’re approved. Why? Because real-world outcomes don’t always match lab results. Patients report different skin reactions, inconsistent pain relief, or unexpected side effects. And brand-name companies aren’t helping. In 2022, the FDA received over 1,200 citizen petitions challenging TE codes-up 17% from the year before. Most come from manufacturers trying to block generic competition for profitable, complex drugs.

State Laws Turn FDA Codes Into Legal Rules

The FDA assigns the codes. But state pharmacy boards decide if substitution is allowed. All 50 states and D.C. base their substitution laws on the Orange Book. If a drug has an ‘A’ code, substitution is permitted. If it has a ‘B’ code, substitution is prohibited. For example:- California - Business and Professions Code §4073 explicitly says pharmacists can only substitute drugs with ‘A’ ratings.

- New York - The Office of the Professions requires pharmacists to consult the current Orange Book edition before any substitution.

- Texas - Allows substitution only if the generic is listed as ‘A’ and the prescriber hasn’t written “dispense as written.”

What Happens When a Code Changes?

TE codes aren’t permanent. The FDA updates the Orange Book every month. If a manufacturer submits new data proving a previously ‘B’-rated drug is actually equivalent, the FDA can upgrade it to ‘A’. One famous example: Zydus Pharmaceuticals’ generic version of the asthma inhaler Albuterol. Originally rated ‘BX’ due to delivery concerns, after years of testing and FDA review, it was upgraded to ‘AB’ in 2021. That single change opened the door for widespread substitution and saved patients millions. But changes take time. The average time from ANDA approval to TE code assignment is 10.3 months. For complex drugs, it can stretch to 18.7 months. Pharmacists must stay updated. Out-of-date Orange Book printouts or unlinked digital systems can lead to illegal substitutions-or missed opportunities to save money.

What You Should Know as a Patient

You don’t need to memorize TE codes. But you should understand this:- If you’re prescribed a generic and it looks different from your last refill, that’s normal. Different manufacturers make different versions.

- If you notice a change in how the drug works-side effects, effectiveness, or how it feels-you should tell your doctor or pharmacist. It could be a formulation issue.

- Ask your pharmacist: “Is this generic approved for substitution?” They can check the Orange Book in seconds.

- Don’t assume all generics are equal. Only those with ‘A’ codes have been proven interchangeable.

What’s Next for Therapeutic Equivalency?

The FDA’s 2023-2027 Strategic Plan aims to cut the number of ‘B’ codes from 24.3% to under 15% by 2027. To get there, they’re investing $28.7 million through GDUFA III to develop better testing methods for complex drugs. New draft guidance released in August 2023 makes it clearer that minor differences in inactive ingredients won’t automatically disqualify a drug from an ‘A’ rating-as long as performance is the same. The Orange Book is also going digital. Since January 2023, it’s been available via API, meaning electronic health records can pull real-time TE code data. Soon, pharmacists won’t need to open a separate website-they’ll see the code right in their dispensing software. This isn’t just about money. It’s about access. More ‘A’ codes mean more patients can get affordable meds without risking their health.Can a pharmacist substitute a generic drug without my permission?

Yes, if the drug has an FDA ‘A’ therapeutic equivalency code and your doctor hasn’t marked the prescription as “dispense as written.” Pharmacists are allowed-and often encouraged-to substitute to save money. But if the code is ‘B’, they cannot substitute, even if you ask.

Why do some generics cost more than others if they’re the same drug?

Even if two generics have the same active ingredient, they can have different TE codes. One might be ‘AA’ (proven equivalent), another ‘AB’ (later proven equivalent), and a third ‘BX’ (not approved for substitution). Manufacturers with newer or harder-to-make versions may charge more. Also, insurance formularies often favor certain generics, which affects price.

Do over-the-counter (OTC) drugs have TE codes?

No. TE codes only apply to prescription drugs approved under Section 505 of the FD&C Act. OTC drugs like ibuprofen or loratadine are regulated under different rules and don’t need FDA therapeutic equivalency evaluations.

Can a drug have an ‘A’ code in one strength but a ‘B’ code in another?

Yes. Therapeutic equivalence is determined by strength and dosage form. A 10mg tablet might be rated ‘AA’, while the 20mg version of the same drug could be ‘B’ if the higher dose doesn’t show bioequivalence. Always check the exact strength you’re prescribed.

What happens if a pharmacist substitutes a ‘B’-coded drug?

It’s illegal. Pharmacists who substitute a ‘B’-coded drug without authorization risk losing their license. If you receive a substituted drug with a ‘B’ code, ask your pharmacist why. You have the right to get the prescribed brand or an ‘A’-coded generic.

Shivam Goel

November 24, 2025 AT 17:09AA, AB, BX-this isn't science, it's a bureaucratic maze wrapped in a legal shell. I've seen generics with the same TE code behave differently across batches. The FDA doesn't test for long-term effects, only peak plasma concentration. That's not equivalence-that's statistical gymnastics.

And don't get me started on how manufacturers game the system: tweak the filler, submit new data, get an 'A' code, then jack up the price. The Orange Book is a living document… written by lawyers with a spreadsheet.

My cousin took a 'AA'-rated generic for hypertension. Lasted three weeks. Then her BP spiked. Switched back to brand. Normal. The FDA's bioequivalence thresholds? 80-125% AUC. That's a 45% swing in exposure. You'd never accept that in a car engine. But in your bloodstream? Sure, why not.

And yes, I've checked the Orange Book. I've also checked the adverse event reports. The 'B' codes are the tip of the iceberg. The real problem? The FDA doesn't track outcomes after substitution. Only approval.

They call it 'therapeutic equivalence.' I call it 'regulatory theater.' And the pharmacists? They're just following the rules. The system is broken. It's not their fault. It's the code.

It's not about money. It's about control. Who gets to decide what works? The FDA? The manufacturer? The insurance company? Or the patient who actually has to swallow the damn pill?

I've seen patients on 'AB' generics for years with zero issues. I've seen others crash on 'AA' ones. The data is noisy. The rules are rigid. That's not safety. That's stagnation.

And now they're going digital? Great. So now the pharmacy software will auto-reject 'B' drugs. But what if the API is down? What if the code was updated yesterday and the system hasn't synced? You think a nurse in rural Nebraska is gonna catch that?

They're not fixing the problem. They're automating the illusion of safety.

And don't tell me 'it saves billions.' It saves billions for insurers. Not for patients. I've seen copays go up after generics hit the market. Because now they're the only option.

Real equivalence? That's not a letter. It's a lived experience. And the FDA doesn't collect those.

Archana Jha

November 25, 2025 AT 11:57ok so here's the truth no one will tell you the orange book is a front for big pharma to keep generics out the real reason some drugs are bx is because the big companies paid the fda to delay approval they dont want you to save money and the te codes are just a distraction to make you think its science when its all lobbying and backroom deals also did you know the fda gets funding from pharma companies?? yeah thats right they get paid by the very people theyre supposed to regulate so of course theyll give a bx to a cheap generic that might work better than the brand

and the 'complex drug initiative'?? lol its a joke theyve been saying that since 2010 and the % of b codes is still rising

also why do all the 'a' coded generics taste different?? that's not science thats placebo effect or maybe the fillers are laced with something

ask your pharmacist if they've ever been pressured to switch you to a cheaper one even if you felt worse

they'll say no but theyll be lying

Aki Jones

November 25, 2025 AT 21:20Let’s be clear: this entire framework is a regulatory fiction designed to maintain monopolistic pricing under the guise of patient safety. The FDA’s 'bioequivalence' thresholds are laughably lenient-80–125% AUC? That’s not equivalence. That’s a statistical loophole engineered to permit market entry without clinical validation. The fact that this is codified into state law is a gross dereliction of duty.

And let’s not pretend that the 'A' rating is a stamp of reliability. We have case studies where patients on identical 'AA'-rated generics experienced wildly divergent outcomes-sometimes due to excipient variability, sometimes due to manufacturing inconsistencies, sometimes due to… well, we don’t know because post-market surveillance is virtually nonexistent.

The digital API rollout? A distraction. It doesn’t fix the underlying flaw: the FDA doesn’t validate clinical equivalence. It validates pharmacokinetic similarity under idealized conditions. Real people don’t live in controlled trials. They have comorbidities. They take other meds. Their kidneys don’t function at 100%.

And the citizen petitions? Of course they’re up 17%. Why? Because the profit margins on complex generics are still too high for Big Pharma to let go. The 'B' codes aren’t scientific-they’re financial barriers disguised as safety protocols.

They’re not saving $298 billion. They’re shifting $298 billion from pharmaceutical manufacturers to insurers and pharmacy benefit managers. Patients still pay more out-of-pocket. The system isn’t designed for you. It’s designed for balance sheets.

And yet, we’re supposed to trust this?

It’s not a system. It’s a spectacle.

Andrew McAfee

November 27, 2025 AT 11:49Arup Kuri

November 27, 2025 AT 15:27You people are naive. The FDA doesn't care if you live or die. They care about paperwork. That 'A' code? It's just a stamp they give after you pay $10 million in testing fees. The real test? Does the generic make the brand-name company nervous? If yes, it gets a 'B'. If no, it gets an 'A'-even if it's made in a factory with rats in the walls.

I've seen generics from the same company with different TE codes. Same active ingredient. Same dose. Different fillers. One's 'AA'. One's 'BX'. Why? Because the 'BX' version was made in a different plant. And the FDA doesn't care about the drug. They care about the paperwork.

And don't tell me about 'cost savings'. I've seen patients pay more for a 'AA' generic than the brand because the insurance company only covers one version. The system isn't designed to help you. It's designed to confuse you so you stop asking questions.

And the 'digital API'? That's just another way for them to track you. Every time a pharmacist checks the code, it gets logged. Who's watching that data? Big Pharma. Insurance. The government. You think they're doing this for you? No. They're doing it to control you.

Wake up. This isn't science. It's surveillance.

Timothy Sadleir

November 28, 2025 AT 02:11It is imperative to underscore that the therapeutic equivalency framework, while imperfect, remains the most robust, evidence-based, and legally codified mechanism currently available to ensure pharmaceutical safety and accessibility across the United States.

The assertion that bioequivalence thresholds are arbitrary is misleading; the 80–125% confidence interval for AUC and Cmax is derived from decades of pharmacokinetic research and international consensus, including guidance from the EMA and Health Canada.

Moreover, the fact that 97% of generic prescriptions involve 'A'-rated drugs speaks not to systemic failure, but to the efficacy of the Hatch-Waxman framework in promoting competition without compromising clinical outcomes.

The anecdotal reports of variable patient responses are valid, but they do not invalidate population-level data. The FDA's post-market surveillance system, including MedWatch and the Sentinel Initiative, actively monitors adverse events associated with substitution.

It is also worth noting that the decline in review times-from 34 to 22 months-is a remarkable achievement in regulatory science, especially given the complexity of novel delivery systems.

To dismiss this entire system as 'regulatory theater' is not only intellectually lazy, but dangerously dismissive of the thousands of scientists, pharmacists, and regulators who dedicate their careers to ensuring that every pill dispensed is both safe and effective.

The goal is not control. It is care.

Srikanth BH

November 29, 2025 AT 23:31Hey, I just want to say-this whole system is actually pretty cool when you think about it. It’s not perfect, but it’s trying. I’ve been a pharmacist for 18 years and I’ve seen generics go from being looked down on to being trusted by patients. That’s huge.

And yeah, sometimes a patient says, ‘This one doesn’t feel right.’ And we listen. We don’t just swap because the code says so. We talk. We check. We call the doctor. That’s the human part they don’t talk about in the Orange Book.

It’s not about big pharma or government control. It’s about making sure someone with diabetes, or asthma, or high blood pressure can get the medicine they need without going broke.

So yeah, the codes are technical. The process is slow. But every time someone gets a $5 generic instead of a $500 brand, that’s a win.

Keep asking questions. Keep checking. But don’t give up on the system. It’s working-for millions of people.

Jennifer Griffith

November 30, 2025 AT 09:56Kimberley Chronicle

December 2, 2025 AT 09:33There’s a fascinating tension here between regulatory rigor and real-world variability. The TE codes are an elegant solution to a messy problem-standardizing substitution across 50 states with thousands of manufacturers and formulations.

But what’s missing is patient-reported outcomes. We measure AUC and Cmax, but not quality of life, adherence, or subjective symptom control. That’s a blind spot.

Imagine if the Orange Book integrated anonymized patient feedback into the rating system. A drug with an 'AA' code but 30% of users reporting reduced efficacy? That should trigger a review.

And the digital API? Brilliant. But it needs to be linked to EHRs with alerts for patients who’ve previously had adverse reactions to a specific generic manufacturer.

This isn’t just about science. It’s about designing systems that learn from lived experience.

Let’s not just fix the code-let’s make it smarter.

Pallab Dasgupta

December 4, 2025 AT 05:39Bro. I just want my meds to work. I don't care about A's and B's. I care that I'm not throwing up at 3 a.m. because my 'AA' generic is made with a filler that gives me acid reflux. I've been on 4 different generics of the same drug. Three of them made me feel like a zombie. One? I felt like myself again.

And guess what? They all had the same damn TE code.

So stop talking about regulations. Talk about the damn pills. Who's testing this stuff in real people? Not the FDA. Not the manufacturers. We are. The patients. The ones who have to live with the side effects.

I'm not mad at the pharmacist. I'm mad at the system that says 'it's the same' when it's clearly not.

Next time you get a new generic? Don't just take it. Test it. Track it. Tell your doctor. Tell your pharmacist. Tell someone.

Because if no one speaks up, nothing changes.

Emily Craig

December 5, 2025 AT 00:09Karen Willie

December 5, 2025 AT 23:18For anyone feeling overwhelmed by the TE code system-you're not alone. But here's what you can do: keep a small notebook. Write down the name of the generic, the manufacturer, how you felt, any side effects. Over time, you'll start to notice patterns.

Some manufacturers consistently work better for you. That's not magic. That's formulation. And you have the right to ask your pharmacist for the one that works.

It's okay to say, 'I need the one from Company X.' You're not being difficult. You're being smart.

And if you're a patient who's been told 'it's the same'-it's not always true. And you deserve better.

You're not crazy. You're just paying attention.